April 23, 2012

Subscribe to the Commodore Nation | April issue

by Rod Williamson, Director of Communications

|

| Roy Kramer (above) brought George Bennett to Vanderbilt to reorganize the National Commodore Club. |

On October 16, 1931, Clemson lost a disappointing 6-0 football game to The Citadel. Afterwards, former Vanderbilt captain and then-Tiger Head Coach Jess Neely lamented that if he just had a few scholarships he felt he could be successful.

Dr. Rupert Fike decided to do something about it and, working with some other interested boosters, organized the IPTAY Club, the first collegiate athletic fundraising organization in the nation. IPTAY is an acronym for “I Pay Ten a Year,” a modest start to a club that would be raising in excess of $14 million per year by the turn of the century.

While the number of zeros at the end of that annual fund goal has grown steadily over the decades, some things don’t change. Coaches and the administrators that oversee their programs still look wistfully to development as an important element in the winning formula.

It can be a delicate dance. While some boosters grasp the need to contribute and loyally make donations that help collegiate athletic departments tick, others appear to have a deaf ear to the significance their potential gift could have on their school’s success.

There was a time–certainly back in those formative days of Jess Neely, Dan McGugin and, to a large extent, even the Roy Skinner era in the 1960s and early 1970s–when a university was able to field competitive teams in its athletic department without needing to pass the hat. It would be wonderful if that were still the case but those days are gone with the wind.

As football and basketball programs began to flourish in the 1970s, universities began to realize that outside financial help was needed. The decision didn’t come easily on any college campus, however, since athletic directors feared that once their schools began accepting outside donations they would become beholden to these donors.

Roy Kramer became Vanderbilt’s Director of Athletics in 1978 and it didn’t take the future Southeastern Conference Commissioner long to realize that to make the kind of headway alumni expected, he would need to find additional sources of revenue.

|

| George Bennett |

Expenses were rising. Around the country, salaries and travel costs were escalating. In the Midwest, for example, Iowa State had just lured Michigan’s Johnny Orr to its basketball program for the then princely sum of $60,000, plus some perks. Football teams had long since abandoned train or bus travel to far-away games and some charter flights were costing $20,000 or more!

Kramer saw the trends and turned, somewhat ironically, to the same Clemson/IPTAY Club that Jess Neely had spawned. Forty-eight years after that famous IPTAY formation, Kramer hired George Bennett to become the Executive Director of the National Commodore Club.

Bennett had overseen IPTAY for eight years and the Tigers were generating significant gift income. He found a very different landscape at Vanderbilt.

“When I arrived, the NCC had about 600 members with total giving around $200,000,” Bennett recalled recently. “There were quite a few little quarterback clubs but it was not their purpose to raise significant dollars. I spent three weeks at the Holiday Inn forming a new plan for Vanderbilt based upon my Clemson experience and then realized it was a big mistake because of the differences in alumni bases. Vanderbilt alums were just too scattered.”

Bennett told Kramer that the goal was “to become the best mail order organization we could be.” They decided to disband the existing Commodore Club and start over.

It wasn’t easy. While some Vanderbilt alumni promised that “when you get athletics straightened out to where we can be proud of it, we’ll start donating money,” there were skeptics on nearly every corner. Those doubters included some members in the media, who wondered just what was happening on West End and why it was necessary.

“We asked people if they wanted us to have women’s athletics,” Bennett remembers. “We asked them if they’d prefer to watch the Sigma Nu’s play the Sigma Chi’s or if they’d rather watch Vanderbilt play Kentucky head-to-head. Some people got on board quickly, others took much more time.”

Bennett remembers the big hill Kramer and Company had to climb to get the Commodores back in the Southeastern Conference mix.

“We had the worst weight room in America at the time,” Bennett recalled. “We didn’t even take our recruits there on their visit. We worked hard to build a new stadium where old Dudley Field had stood since 1922. We used men’s basketball as our hub because those tickets were a hot item. If you lived in Nashville and didn’t vacation in Florida or attend Commodore games you were out of the social order. We tried to clean up our priority ticket policy.”

Within a year or two, Vanderbilt was raising $1 million for its athletic scholarships, thus freeing up other dollars to make much needed advancements elsewhere in the department. Before Bennett would leave in 1986, Vanderbilt would be raising approximately $2 million per year.

Inflation: A Tough Opponent

That $2 million went into the athletic scholarship fund during a time when the scholarship was valued at approximately $10,000 per year. That meant that the gifts of alumni and friends nearly met the department’s total scholarship tab.

Times have changed. That same full scholarship–tuition, board and books–costs $58,000 in 2011-12, making the athletic department’s total scholarship obligation for about 205 scholarships $12 million for the year. It would take a contribution of $600 today to equal the impact of that $100 gift back in the Kramer-Bennett days.

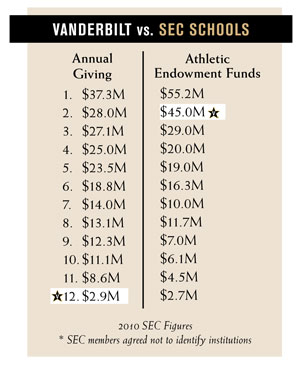

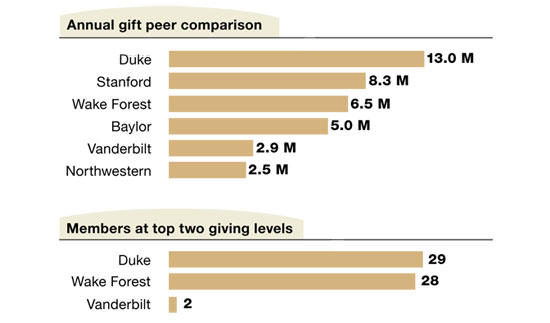

While the scholarship expenses have steadily increased over the years, annual giving unfortunately has not kept pace. Over the past five fiscal years, annual giving to the National Commodore Club has not cracked $3 million a single time, hovering between $2.7 and $2.9 million.

While the scholarship expenses have steadily increased over the years, annual giving unfortunately has not kept pace. Over the past five fiscal years, annual giving to the National Commodore Club has not cracked $3 million a single time, hovering between $2.7 and $2.9 million.

The downside of this flat-line giving has been mitigated to some degree by the department’s success in building up its athletic endowment. While Vanderbilt ranks last in the Southeastern Conference in annual giving by a wide margin, it has the second largest athletic endowment in the league, one that spins off about $2 million per year.

Vanderbilt’s athletic endowment–a subset of the university’s much bigger endowment–has been bolstered by generous friends of the department and a disciplined philosophy and recognition that a bigger “savings account” would pay dividends throughout the future.

Adding the endowment income with annual gifts still leaves a $7 million gap toward that $12 million scholarship tab, which means that monies that theoretically could have been allocated for improvements elsewhere must be funneled into scholarships to make up the difference. That has restricted what can be done to improve the Commodore athletic brand.

Bold Plans to Meet Tough Challenges

Vanderbilt Athletics has a wide array of capital projects in motion, so in addition to annual giving and endowment, there is an urgency to identify major gifts. In recent months, a number of impressive enhancements have been finalized and are expected to be in place by summer’s end; they include:

· New lights for Vanderbilt Stadium

· New Jumbotron for Vanderbilt Stadium and Memorial Gym

· Sports turf on Vanderbilt Stadium

· Sports turf on Hawkins Field

· Phase II renovation to McGugin Center

These are big-ticket items totaling around $35 million. In addition to this list there are several other projects that will impact our golf and cross country programs that also require external financial assistance.

Aside from these major projects that are necessary to keep us competitive in the nation’s most challenging athletic conference, there are other burning financial needs. Expenses have soared over the years.

That “expensive” $20,000 football charter flight in 1975–the one that carried a traveling party of 125 people halfway across the United States–now costs $120,000! Short basketball season charter trips now cost $20,000, often more. Big-time coaches are no longer paid $60,000 a year. The cost for scholarships has tripled since the days of President Nixon.

Next Level Offers New Options, New Solutions

Under the direction of Mark Carter, executive director of the National Commodore Club and athletic development, new initiatives have recently been introduced as Commodore athletics strives for the “Next Level.”

|

| Six Steps of Next Level Support

1. Buy season tickets, wear black and gold with pride and attend games |

While the NCC encourages unrestricted gifts that can be applied for tuition, fees and board, one new giving opportunity recently rolled out allows fans to make restricted gifts earmarked for a specific varsity team.

“We realized that some people feel very good about giving to a particular team,” Carter says. “A tennis letter winner, for example, probably wants to support the tennis program. Now for the first time through the National Commodore Club, we have created an attractive way for that to happen.”

Carter, who is in his second year at Vanderbilt after coming from a highly successful tenure at Duke in a similar capacity, says that there is plenty of room for everyone to participate.

“We’ll occasionally run into a friend of our program that feels like his or her small gift doesn’t make a difference,” he says. “We point out that every gift makes a difference. While it may appear that we are only seeking major gifts, it is really the rank and file donor that is our foundation and driving force. We have plenty of room inside our tent and we are eager to expand our base.”

The National Commodore Club has two relatively new, upper levels of giving. The McGugin Society is designed to cover the costs of one full scholarship for a year; this year that was $58,863. The Dudley Society covers the cost of one year of tuition ($40,315). If Vanderbilt was to add just five new members to each Society, the resulting $497,840 would have a real impact.

In the end, the decision to donate is a personal choice, one that as a reader of this magazine you have already made. There are others, some friends and neighbors, who to this point have chosen not to participate and wonder why they should.

When one makes a charitable contribution, that gift tends to make the relationship more permanent. That gift transfers a form of psychological ownership, an ownership of the heart and soul. That is a rock solid foundation for success.